Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Queer Blues: The Hidden Figures Of Early Blues Music

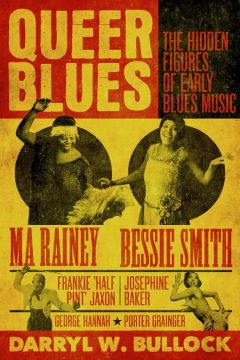

Queer Blues: The Hidden Figures Of Early Blues Music

Queer Blues: The Hidden Figures Of Early Blues Music

Queer Blues: The Hidden Figures Of Early Blues Music Darryl W. Bullock

352 Pages

ISBN: 978-1-9131-7252-7

Omnibus Press

2023

The blues is ripe with legends and myths, not least the oft-touted claim that W.C. Handy was the father of the blues. But as Darryl. W. Bullock tells it, there is an important tract of blues history that has not got its due. Until now. In his telling, many of the blues pioneers were women and men living openly LGBTQ lives.

But Queer Blues... is more than just an alternative history of the blues; in fact, one comes away from these 350-plus pages with the impression that the first decades of the 20th century represented not just a revolution in popular music, but in queer history as well.

Avoiding the trap of a simplistic, reductive narrative, Bullock instead acknowledges the deep and convoluted roots of the blues—roots that cross-pollinated with jazz from early on. Traveling tent shows, vaudeville theatre and urban rent parties were all incubators and platforms for the blues. Many of the stars of these various performance spaces were initially referred to as "coon shouters" or "moaners" before the term "blues" became commonplace.

Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, two of the most prominent figures in Bullock's history, honed their craft in these settings, particularly on the tent-show circuit, where they reached large and devoted audiences. Their records sold in the tens of thousands.

For the author, the rapid growth of an identifiable LGBTQ culture in Northern US cities was bound up with the Great Migration of the early decades of the 20th century. In the first major wave, millions of black Americans abandoned the life-threatening racism and bitter poverty of the Southern states for a better life in the Northern cites. That much has been well chronicled.

Few music historians, however, have paid attention to the transformative effect the migration had on LGBTQ people. Bullock recounts how this mass relocation created the conditions for many LGBTQ people to find their own community and their own support networks. In short, a social and cultural life that was unthinkable in the South.

As such, the book's parameters go well beyond the blues, covering queer entertainers and locales in all their rich variety, from female impersonators, lesbian and gay bars, LGBTQ-friendly clubs, and drag balls.

It is a story that acknowledges and celebrates the successes of early queer entertainers. Theirs is a gallery so colorful that stars like Andrew Tribble, a female impersonator, Guilford "Peachtree" Payne, alleged hermaphrodite, Frankie "Halfpint" Jaxon, a vaudeville singer or Gladys Bentley, a black, lesbian, cross-dressing blues singer/pianist, would be worthy subjects of a Hollywood biopic.

Another arena where the blues and LGBTQ people intersected was at buffet parties, otherwise known as rent parties. Held in private homes, for a small entrance fee party goers could find cheap booze and all kinds of entertainment, from dancing to performance sex. At these parties, which thrived during Prohibition, blues records were common. This, the author states, played an important role in spreading the blues from the tent show and vaudeville circuits into people's homes.

Besides Smith and Rainey, Bullock gives ample space to many other pioneering figures, among them Alberta Hunter, Porter Grainger, Ethel Williams, Mabel Hampton, Tony Jackson, Clara Smith, Lovie Austin (one of few black women who fronted her own band) and Josephine Baker. All led openly lesbian or gay lives.

Maude Russel, a friend of Josephine Baker, inferred that the brutality of the male patriarchy meant that for many women female companionship was preferable. Her words, quoted by the author from the Jean Claude Baker and Chris Chase biography Josephine: 'The Hungry Heart' (Harper and Row, 1977) are worth quoting at length:

"Well, many of us had been kind of abused by producers, directors, leading men—if they liked girls. In those days men only wanted what they wanted, they didn't care about pleasing a girl. And girls needed tenderness, so we had girl friendships, the famous lady lovers, but lesbians weren't well accepted in show business, they were called bull dykers. I guess we were bisexual, is what you would call it today."

The aforementioned Gladys Bentley had two children by the age of 13, both by rape, which she gave up for adoption. Little wonder then that some women favored female relationships

These artists' songs, often bawdy and explicit in nature, reflected their lifestyle and sexual preferences. Bullock addresses dozens of the most pertinent examples, including Lucille Bogan's "Women Won't Need No Men," Ma Rainey's "Shave 'Em Dry Blues" and Kokomo Arnold's "Sissy Man Blues."

Any notion that the LGBTQ lifestyle in American cities in the early decades of the 20th century was one big party is swiftly dispelled by the author. Prohibition's moral crusaders also had the LGBTQ community in its crosshairs. Invasive, even sadistic media scrutiny was the thin edge of the wedge. In the Chicago of the 1910s, we learn, vagrancy laws provided ..." an excuse to arrest anyone suspected of being LBGTQ for decades to follow."

Anti-LGBTQ violence and police harassment/corruption were a daily threat. One photo captures leering crowds jostling to peer inside a police wagon full of recently arrested cross-dressers. Such inequities, however, paled in comparison to the dangers of the Southern states. On one occasion, the corpse of a lynched black man was dumped in the foyer of a Georgia theatre where Ethel Waters was playing.

When seen in the light of the endemic racism and prejudice faced by black/LGBTQ artists, their successes are indeed something to celebrate.

Ethel Waters, who appeared with Duke Ellington at The Cotton Club, was reputedly the first black woman to sing on public radio. She was also a featured singer in On With The Show (1929), the first all-talking, all-color feature-length film. And when Irving Berlin cast her for the musical As Thousands Cheer (1933), Waters became the first black star to share equal billing with white actors.

Josephine Baker went one better, enjoying international stardom. Her success in London and Paris in 1923, where she was hailed as "the finest jazz dancer in the world," ushered in a wave of black American stars who ventured to perform all over Europe.

As for the early, classic blues singers, Bullock relates, without sentimentality, how they fell victim to changing times and changing tastes. Ma Rainey never recorded again after 1929. In 1931 Columbia dropped Bessie Smith for low record sales. Male-dominated blues was taking over. In her last years, Rainey owned three theatres in her hometown of Columbus, Georgia. Smith never came off the road, continuing to play to enthusiastic audiences in tent shows and theatres until she died in a car crash at the age of 43.

Meticulously researched, Bullock's engaging account of the lives and times of the early blues LGBTQ pioneers has the convincing ring of historical truth about it that should invite a rethink on dominant blues histories. Above all, though, it is a story of women and men of bold artistic and personal convictions that will likely serve as an inspiration to many.

< Previous

Wonder Is The Beginning

Next >

Underbrush

Comments

Tags

Book Review

Bessie Smith

Ian Patterson

W.C. Handy

Ma Rainey

Gladys Bentley

Alberta Hunter

Porter Grainger

Ethel Williams

Mabel Hampton

Tony Jackson

Clara Smith

Lovie Austin

Josephine Baker

Maude Russel

Lucille Bogan

Kokomo Arnold

duke ellington

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.